How To Launch Big Complex Projects

How to reduce costs and schedule overruns, manage risks and be prepared for an unlucky turn of events.

Think about your past projects. Did they finish on time? Did they get delivered without cutting corners? Chances are high that they haven’t. Perhaps they got delayed, moved, cancelled, “refined” or postponed. As it turns out, in many teams, shipping on time is an exception, rather than the rule.

Things almost never go according to the plan — and on complex projects, they don’t even come close. So how can we prevent it from happening? Well, let's find out.

99.5% Of Big Projects Overrun Budgets And Schedules #

As people, we are inherently over-optimistic and over-confident. It’s hard to study and process everything that can go wrong, so we tend to focus on the bright side. However, unchecked optimism leads to unrealistic forecasts, poorly defined goals, better options ignored, problems not spotted, no contingencies to counteract the inevitable surprises.

The blue line follows a normal distribution, the red line follows “fat tails” — sometimes big outliers are quite common. Image source.

Hofstadter’s Law states that the time needed to complete a project will always expand to fill the available time — even if you take into account the Hofstadter’s Law. Put differently, it always takes longer than you expect, however precautious you might be.

As a result, only 0.5% of big projects make the budget and the schedule — e.g. big relaunches, legacy re-dos, big initiatives. We might try to mitigate risk by adding 15–20% buffer — but it rarely helps. Many of these projects don’t follow “normal” (Bell curve) distribution, but are rather “fat-tailed”.

And there, overruns of 60–500% are typical and turn big projects into big disasters.

Reference-Class Forecasting (RCF) #

We often assume that if we just thoroughly collect all the costs needed and estimate complexity or efforts, we should get a decent estimate of where we will eventually land. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Complex projects have plenty of unknown unknowns. No matter how many risks and dependencies and upstream challenges we identify, there are many more we can’t even imagine. The best way to be more accurate is to define a realistic anchor — for time, costs and benefits — from similar projects done in the past.

IT projects are more likely to have a fat-tailed distribution, with extreme outliers.

Reference-class forecasting follows a very simple process:

- First, we find the reference projects that have most similarities to our project,

- If the distribution follows the Bell curve, use the mean value + 10–15% contingency.

- If the distribution is fat-tailed, invest in profound risk management to prevent big challenges down the line.

- Tweak the mean value only if you have very good reasons to do so.

- Set up a database to track past projects in your company (for cost, time, benefits).

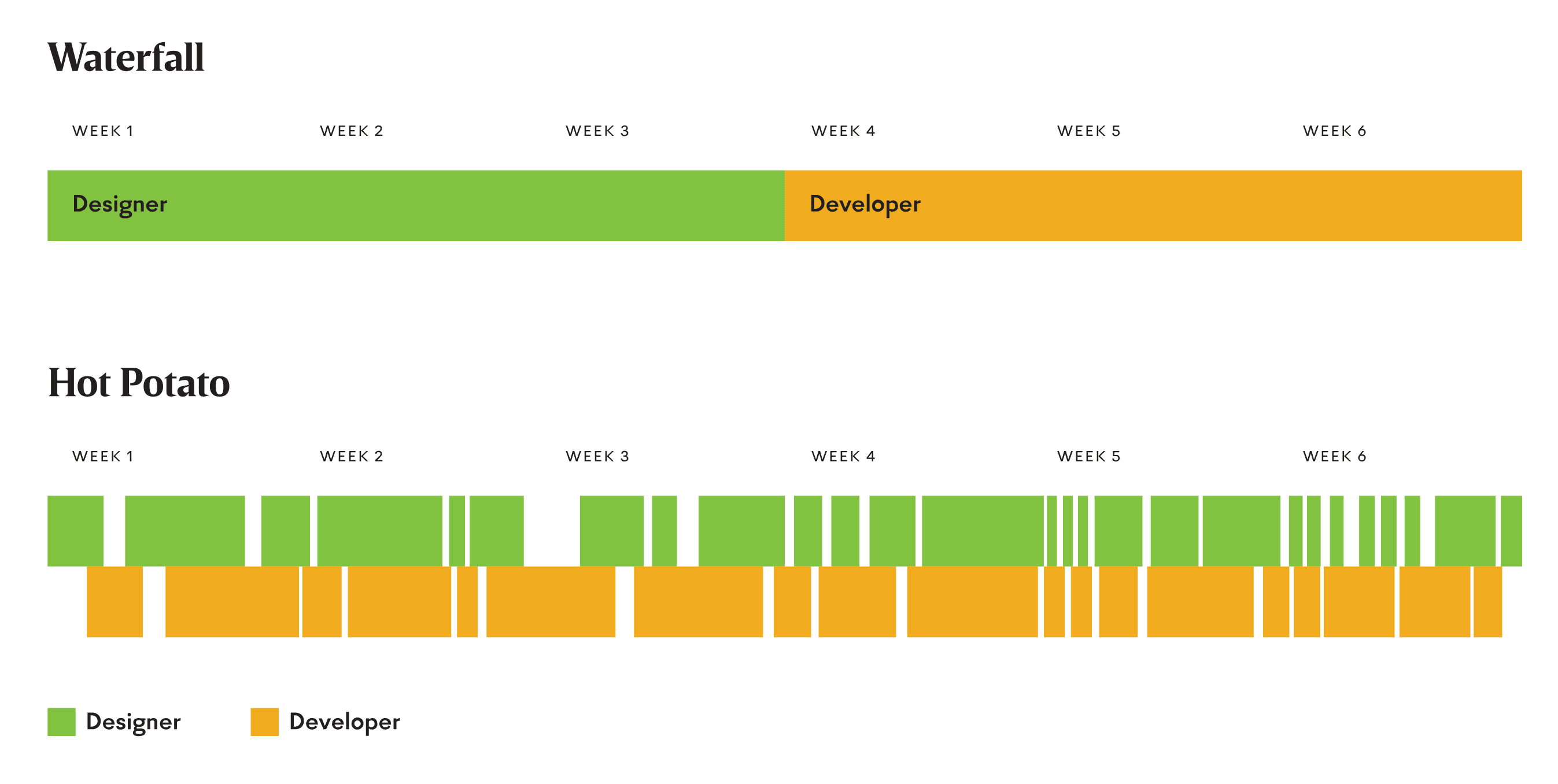

Think Slow + Act Fast #

In spirit of looming deadlines, many projects rush into delivery mode before the scope of the project is well-defined. It might work for fast experiments and minor changes, but that’s a red flag for larger projects. The best strategy is to spend more time in planning before designing a single pixel on the screen.

But planning isn’t an exercise in abstract imaginative work. Good planning should include experiments, tests, simulations, refinements. It must include the steps of how we reduce risks and how we mitigate risks when something unexpected (but frequent in other similar projects) happens.

In IT, mean cost overrun is around 73%, and 18% have >50% overruns (fat-tailed distribution). Mean overruns of these projects are 447% (!).

Black Swan Management #

Every other project encounters what's called a Black Swan — a low probability, high-consequence event that is more likely to occur when projects stretch over longer periods of time. It could be anything from restructuring teams to change of priorities, which then lead to cancellations and re-scheduling.

Little problems have an incredible capacity to compound to large, disastrous problems — ruining big projects and sinking big ambitions at a phenomenal scale. The more little problems we can design around early, the more chances we have to the project out of the door successfully.

So we make projects smaller and shorter. We mitigate risks by involving stakeholders early. We provide less surface for Black Swans to emerge. One good way to get there is to always start every project with a simple question: “Why are we actually doing this project?” The answers often reveal not just motivations and ambitions, but also the challenges and dependences hidden between the lines of the brief.

And as we plan, we could follow a “right to left thinking”. We don’t start with where we are, but rather where we want to be. And as we plan and design we move from the future state towards the current state, studying what’s missing or what’s blocking us from getting there. The trick is: we always keep our end goal in mind and our decisions and milestones are always shaped by that goal.

Manage Deficit of Experience #

Complex projects start with a deep deficit of experience. To increase the chances of success, we need to minimize the chance of mistakes even happening. That means trying to make the process as repetitive as possible — with smaller “work modules”, repeated by teams over and over again.

🚫 Beware of unchecked optimism → unrealistic forecasts.

🚫 Beware of “cutting-edge” → untested technology spirals risk.

🚫 Beware of unique” → high chance of exploding costs.

🚫 Beware of “brand new” → rely on tested and reliable.

🚫 Beware of “the biggest” → build small things, then compose.

It also means relying on reliable: from well-tested tools to stable teams that have worked well together in the past. Complex projects aren’t a good place to innovate processes, mix-n-match teams and try out more affordable vendors.

Typically, these are extreme costs in disguise, skyrocketing delivery delays and unexpected expenses.

Good Design Is Good Risk Management #

When speaking about design and research to senior management, position it as a powerful risk management tool. Good design that involves concept testing, experimentation, user feedback, iterations and refinement of the plan is cheap and safe.

Eventually it might need more time than expected, but it's much — MUCH! — cheaper than delivery. Delivery is extremely cost-intense, and if it relies on wrong assumptions and poor planning, then that's when the project becomes vulnerable and difficult to move or re-route.

Wrapping Up #

The insights above come from a wonderful book on “How Big Things Get Done” by Prof. Bent Flyvbjerg and Dan Gardner. It goes in all the fine details of how big project fails and when they succeed. It’s not a book about design, but a fantastic book for designers who want to plan and estimate better.

Not every team will work on a large, complex project, but sometimes these projects become inevitable — when dealing with legacy, projects with high visibility, layers of politics or an entirely new domain where the company moves towards.

Good projects that succeed have one thing in common: they dedicate a majority of time in planning and maneuvring risks and unknown unknowns. They avoid big-bang revelations, but instead test continuously and repeatedly.

That's your best chance to succeed — work around these unknowns as you won't be able to prevent them from emerging entirely anyway.