Designing For People With Dementia

UX guidelines for designing for people with dementia, focusing on reduced working memory, scroll fatigue and autonomy. The only limits for tomorrow are the doubts we have today.

Design is often an exercise in resilience. Our products must work for people in any life situations they find themselves. A path there always lies through accessible, inclusive design — that makes it more difficult to make mistakes.

One frequently overlooked condition is dementia. How we can design better experiences for people with severe challenges around memory and thinking? Well, let's find out.

Design with empathy: a powerful approach for developing dementia-friendly products and services. Practical guide PDF.

What Exactly Is Dementia? #

Dementia is a syndrome that significantly affects memory, thinking and social interactions. It affects 55 million people globally and that number will reach 139 million by 2050. Alzheimer's disease is the most common cause for dementia (around 60–80% of all cases).

The syndrome comes slowly and unexpectedly, typically around the age of 65, but early-onset dementia can also occur between 45–65 years (9%). Usually it starts showing in confusion, disorientation, language and difficulty with sequenced actions (like cooking).

A practical overview of UX guidelines on how to design with and for people affected by dementia. Practical guide PDF.

That's when shiny surfaces look wet and dark mats look like holes. And sometimes it's simply forgetting what a microwave beep means. In such situations many people feel incredibly embararassed, so they mask symptoms for months and years — writing extensive notes to "make up" for memory loss or avoiding phone calls.

As dementia progresses, it's becoming impossible to remember recent events or recall information. Following multi-step instructions is hard (e.g. cooking a meal) — but even counting coins or cutting and pasting text can be difficult.

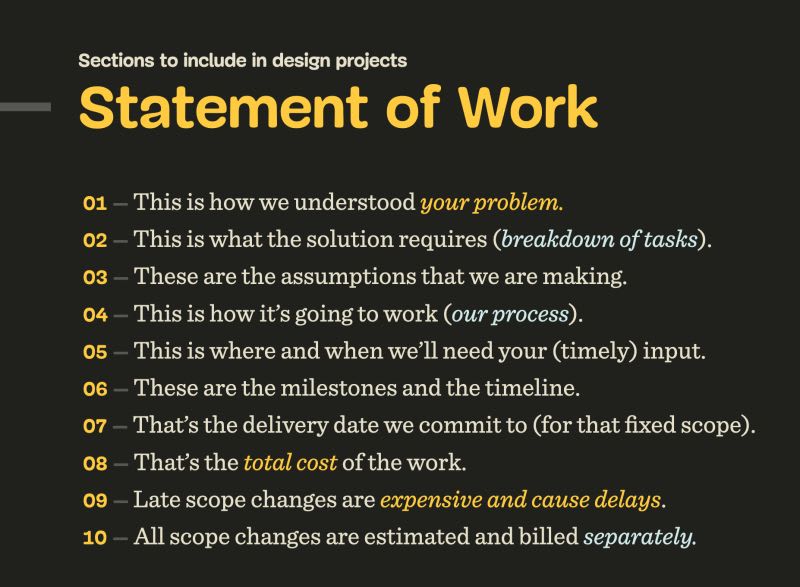

Design Patterns For People With Dementia #

Here are considerations that we need to keep in mind for more inclusive experiences — they are quite broad accessibility needs:

- Avoid auto-moving carousels or moving, flashing content. They are very distracting and are likely to cause task abandonment.

- Don't rely on working memory. Instructions often get lost between the screens. If something is important to know, show it. Keep details needed to act available for look-up.

- Leave traces of what happened. E.g. it's not a good idea to clear search query after it's executed, or use an overlay that covers information that a user needs to reference.

- Avoid patronizing language: "sweetie", "well done", "really good job!".

- Always add text labels to icons, especially the abstract ones. People learn icons, but just as well they forget them and get lost between them.

- Buttons and inputs need borders, min 44×44px touch targets. White buttons with subtle shadow on white background are difficult to spot.

- Test legibility of web fonts. Use the text snippet

1Il0Oto test legibility — individual characters must be distinguishable. Line height of 1.5+ prevents lines from "swimming" together. - Favor left-aligned text: justified text creates "rivers of white" that are highly distracting.

- Avoid generic labels ("Submit", "Confirm", "Proceed"). Better use descriptive, verb-based labels, e.g. "Finish and Send".

- No puzzles/CAPTCHAs: these are cognitive blockers (WCAG 2.2).

- Forgiving inputs: Allowing variations in data entry and toggle passwords for easier access.

Accessible doesn't mean boring. The ambition was to create an accessible, inclusive UX that is also exciting and bold. Wise case study.

A point I'd like to raise is that memory tests, image recognition tests and puzzles proactively exclude people with cognitive disabilities. And, as stated in WCAG 2.2, we need to avoid password-only authentication with alternative ways — password managers, social login and biometric auth. Password-only systems are often cognitive traps for dementia users.

Also, around ~15% of dementia users also have motor impairments or low vision. They navigate entirely with keyboard or adaptive devices. Steph Walter highlighs use cases for cognitive accessibility in post on neurodiversity and UX.

Dignified Experience and Sense of Independence #

When we think about users with dementia, we might instinctively consider a "simple" version of the product that strips all details and all complexities away. However, an oversimplified version is likely to lead to more, not fewer, mistakes.

Users with dementia don't need a barebones version of your product. They need resilient, error-proof paths to follow — with a respectful, helpful, dignified UX and a sense of independence, even if the mind changes frequently.

Wrapping Up #

It's important to understand that dementia fluctuates (good days vs. bad days) but the long-term trajectory is downward. Still, it's a condition where capability can be highly fluid and highly dependent on user's environment. Creating order around tasks helps.

Just like any other group, older users need a reliable, clear product that helps them feel independent and competent. Bring people living with dementia in your design process to find out what their specific needs are.

"Nothing about us without us": you can't design for people without designing with them.

And huge kudos to wonderful people contributing to a topic that is often forgotten and overlooked. 👏🏼👏🏽👏🏾

Useful Resources #

- Dementia Diaries (audio diaries recorded by people living with dementia)

- Free Webinar: Dementia-Friendly Design, by AbilityNet

- Making memory loss easier for families, UX case study, by Sean Rockwood

- Dementia Digital Design Guidelines, by Rik Williams

- Designing for Dementia, by AbilityNet

- Practical guide to designing products for people with dementia, by Alzheimer's Society

- MinD: Designing for People with Dementia

- Designing For Dementia: 9 Tips To Improve Environments

- Dementia-friendly Service Design, by Alzheimer's Society

- DEEP Guide: Language and Dementia

- W3C Cognitive Accessibility Guidance (COGA)